The painter constructs, the photographer discloses.

Susan Sontag

The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.

Dorothea Lange

To photograph is to put on the same line of sight; the head, the eye, and the heart.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

This week I began the audio book `The Lightmaker’s Manifesto’, by Karen Walrond. One of the first things I learned, besides the fact that Karen and I are both passionate photographers, is that the word `photography´ comes for Latin roots which mean `to draw with light´. Discovering this early gem in Chapter One was a very good start; it whetted my appetite for more!

Karen relates that she came out of Junior School convinced that she was not `the creative type´. My experience was similar. Teachers had repeatedly told me that painting, drawing, and singing were not my strengths; that they should be avoided at all costs in order to allow me to concentrate on analytical pursuits. This `uncreative´ label, – I later realised that I am ultimately responsible for all such labels – went unchallenged for several decades. My focus remained on analytical topics; engineering, social sciences, project management, and organisational development, with the related elements such as process engineering, workflow optimisation, value streaming, strategy, leadership, and the like.

As I was given greater responsibility in the respective organisations that employed me, that topic of leadership began to bring out more and more of my intuitive creativity. The focus of my workload shifted for managing operations to leading people. That challenge, in turn, showed me that leadership is, in essence, about bringing out the best in people; their strengths, their ideas, their capacity to work well with each other, their light – in the pursuit of common goals. Leadership, you could therefore say, is also a form of `drawing with light´.

My path in life, despite my best intentions, took me into a field of darkness for many years. This is what happens when we succumb to the malady of substance addiction. Mine took me on a downward spiral to a point, in my early forties, where I became spiritually bankrupt and found myself on the brink of not wanting to live any longer.

Thankfully, a moment of grace propelled me into recognising this and, furthermore, towards asking for and accepting help. A journey of recovery began; a journey which could well be described as one from darkness into light. It was in the early years of this transformation that my love for photography was ignited.

This coincided with the relinquishing of many old, often destructive, and sometimes cherished habits. Fly fishing plays a prominent role in the story of my extended family. This hobby, passionately embraced by generations on both sides, led my maternal grandfather to purchase a fishing lodge on one of Ireland’s foremost salmon rivers, way back in 1936. Since then, family summer holidays have been celebrated there, holidays I enjoyed regularly from birth until leaving school (and Ireland, for that matter) and again during the period when my own children were young.

Like my seven brothers, I was keen and spent much of my time there on the river; sometimes for twelve hours or more on days after a night’s rain, eagerly practising the craft taught me in childhood by my father, who learnt it from his, etc. To my consternation, I was not as good, by far, as some other members of the family, and often felt under pressure to prove myself in the strange ways of unwritten family codes.

A few short years after embracing my new life of recovery, I stood on the riverbank, having landed a fine fresh, glistening sea trout and was just about to smash its head on a stone before stowing it away in my fishing bag, when the reflection of the sunlight from its silvery scales filled my irises and my heart. `What an absolute beauty of creation´, was the thought that crossed my mind, whereupon I released it back into the dark bog waters and watched it frantically disappear upstream at pace.

Having given up angling in this somewhat dramatic and cathartic fashion, I discovered that the satisfaction hitherto enjoyed from bringing home a bag of freshly caught trout was equalled, if not surpassed, by a handful of stunning photographs taken on a day’s hike. Digital photography facilitates this, even if the good quality shots are one in twenty-five, or even one in a hundred. The passion, once ignited, yielded scores of photos each week, which I would then edit with the discerning eye of the visual epicure, discarding more than ninety percent of those initially taken.

During this apprenticeship, the alignment of head, eye, and heart began to evolve. I began to look at the world in a different fashion; in 3D, more consciously, more openly, more engaged; experiencing first hand that: `The camera is an instrument that teaches me how to see without a camera´, as Dorothea Lange so accurately expressed.

Today, each day, I like to take time on my own to explore each new destination. It may be the same path walked the day before, yet it is always new. The river (the great Rhein beside my home) is never the same river, yesterday’s waters now almost about to enter the North Sea; the plants one day further (most easily seen at this time of year), and, perhaps most importantly, I am not the Patrick who walked here yesterday.

In combining my great love of Nature and my deep interest in all aspects of `recovery´ (personal, social, ecological, spiritual, etc.) with photography, I have discovered a vein of creativity which once lay dormant and hidden deep within. Indeed, a further progression is the combining of texts and images, me having rediscovered my passion for writing in the meantime also, as I do in this format of the `Weekly Reflections´.

Karen Walrond quotes Edith Wharton´s observation that: `There are two ways of spreading light; to be the candle or to be the mirror that reflects it´. Karen contends that there is a third option; that we can make light. This is done when we pro-actively use our gifts to serve the world, to activate ourselves and others for collective healing and growth.

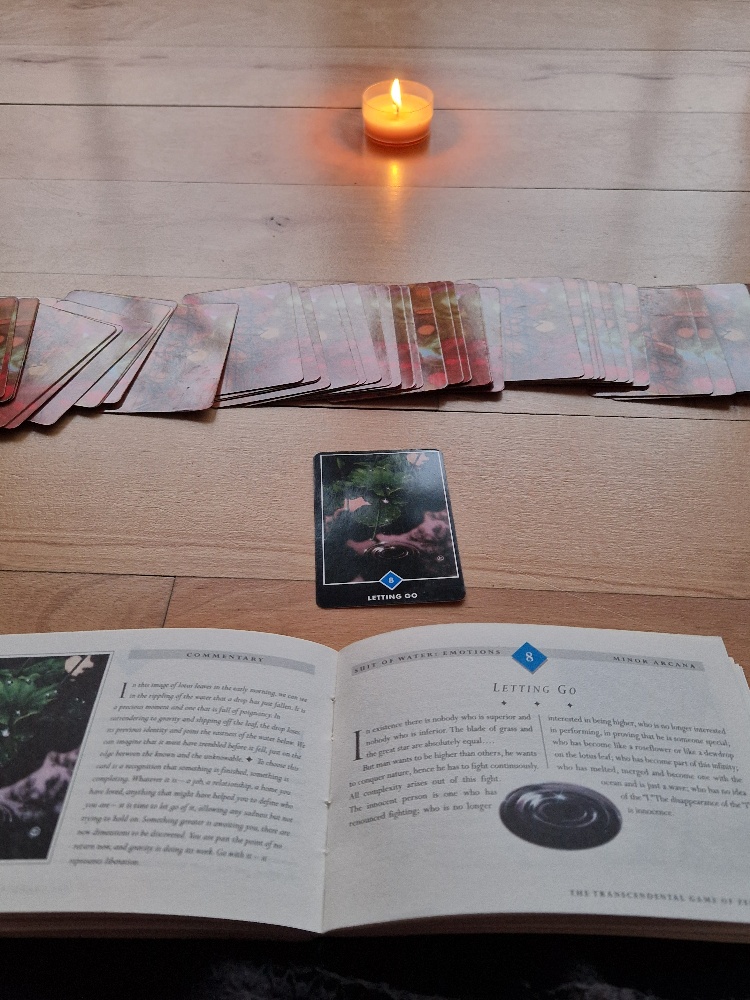

This phenomenon we call `vocation’ or `calling´. The call may come in the form of a bang, or a whisper. In my case a bang led to a whisper. To hear the whisper, we need to be silent, to tune into the frequencies of the Universe. Any practice of meditation enables us to pay attention to the whisper and the intuition deep within us. One of my favourite forms of meditation is photography.