The dead are not distant or absent. They are alongside us. When we lose someone to death, we lose their physical image and presence, they slip out of visible form into invisible presence. This alteration of form is the reason we cannot see the dead. But because we cannot see them does not mean that they are not there.

John O’Donohue, Beauty

Just as when we come into the world, when we die, we are afraid of the unknown. But the fear is something from within us that has nothing to do with reality. Dying is like being born; it’s just a change.

Isabel Allende

I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I live. I rejoice in life for its own sake. Life is no `brief candle´ to me. It is sort of a splendid torch which I have a hold of for the moment, and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it over to future generations.

George Bernard Shaw

At this time of year, the feast of Halloween – `Samhain´ in the Celtic language – coincides with a series of death anniversaries in my family of origin.

The ancients believed that at Samhain (last day of October), the veil separating the world of the living from the world of the dead (Otherworld) became sufficiently thin to allow Otherworld Spirits to mingle with the living. Like most spirits they came in two varieties, evil and benign. The latter were welcomed into homes and honoured through rituals of merriment and feasting.

Evil spirits also made the crossing, and – so our ancestors believed, – would roam the earth searching for souls to take back with them. Consequently, the ancients developed strategies to thwart the evil spirits and thereby avoid being taken prematurely to the Otherworld.

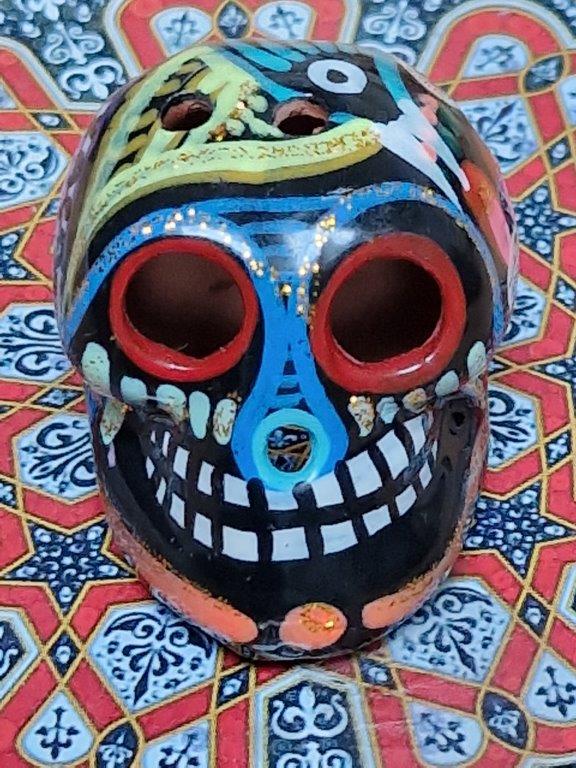

Counter-intuitively, evil spirits were said to be easily frightened by evil looking creatures! Gargoyles and Jack-o‘-lanterns serve exactly this purpose. Our Celtic ancestors created rituals involving icons, masks, costumes, fire, and ancient games to appease any such evil spirits. These rituals were designed to protect us from harm, while acknowledging the presence of all the departed souls which had made it through the veil on the `hallowed evening´. This celebration of ancestral bonds, between those living in this world and all those who have gone before us, is an important milestone in my calendar.

The family anniversaries mentioned above are those of my father, whose soul departed on November 10th, 1977, my mother, on October 25th, 1982, and my oldest brother, sadly missed since November 2nd, 2018.

From today’s vantage point, my dear brother, who died suddenly shortly before his 65th birthday, could be said to have left us while still in late middle age. Even more heartbreaking, then, to remember that Mum and Dad were only 52 and 51 years old respectively, when they breathed their last. At that time, they seemed `old´ to me.

When my father died, I was a grief-stricken, angry, and inconsolable teenager. He had been ill for the best part of a year, cancer spreading throughout his body, and, admiring him greatly and fearing him a little, I seem to remember believing that my great love of him could, should, and would save him. Alas, that was not to be. Young, rudderless, and traumatised, I was not capable of grieving this great loss at that time.

On his passing, my mother was left widowed with six boys at home between the age of 16 and 5. As the oldest living at home, it was expected of me to comfort her and help her in the responsibilities of running a household, etc. In my own grief, I was not up to the task. Her depression meant she was not really present either. When, two years later, the opportunity arose to extract myself from this intolerable situation – to get out of town – I took it; travelling to Germany to work for the summer and then going back to Ireland, to university in Dublin, 200km away from home.

My way of dealing – or not dealing – with my grief; suppression, denial, self-medication, and delusion, was not conducive to academic progress. I dropped out of college after the first year and moved permanently to Germany, where I have lived ever since. I kept in touch with home, by means of coinbox telephone calls and letters, and was glad to be away.

In the summer of my 21st birthday it became clear that Mammy was now also sickly with cancer. Though reluctant to face the painful reality of this situation, I did manage to get home to see her during her few final days. This proved to be very auspicious; it allowed us to clear away much wreckage from the past, to forgive, to re-bond, and to initiate a process of healing, which continued long after her passing. A further twenty years were to pass, however, before real grieving could commence.

My brother, Peadar (Irish for Peter) was eight years my senior. He had been living in the USA since he was a student. As adults, we had had regular encounters at annual family reunions and had visited each others’ homes over the years, but he remained beyond my orbit, and I his, in many respects.

I got to admire his innate kindness under the somewhat gruff exterior and, in the years before he died, I had made my peace with any unresolved childhood experiences concerning us. Though he had been having cardiac issues for some time, it came as a great shock when the sad news of his sudden passing was conveyed to me. His death initiated a process in our generation which I had observed with great interest in my parent’s respective groups of siblings, where we had witnessed them return, one by one, from whence they came. Peadar’s passing brought me face to face with my own sense of mortality.

A few things have become clear to me over the years with respect to my encounters with death. The first is that grieving in not something for me to do, but rather to be. The simplicity of this truth is powerful. The opportunity is to learn to allow all those feelings, activated by irretrievable loss, to well up to the surface, again and again, and simply be there. By allowing them to be, they become fuel for healing and growth. It took me a long time to realise this and put it into practice. It has proved very liberating.

My father’s death and, in particular, how he handled the experience, has also shown itself to be a great gift. By leaving this incarnation in a conscious state of humility, faith, and gratitude, he demonstrated how best we can embrace the ultimate human challenge. Almost half a century later, I still find myself unwrapping further layers of this precious gift.

I finally stopped self-medicating in 2003. Over the past twenty years of inner work, I have had the good fortune of using the family constellation modality developed in recent decades. This has been a powerful healing experience. One of the main takeaways has been that the best possible way to honour those who have gone before us is to now live our own lives to the full. I know that that is what my loved ones would want for me, and I feel their support as I move in this direction. As John O’ Donohue puts it so elegantly: `They continue to be near us; part of the healing of grief is the refinement of our hearts whereby we come to sense their loving nearness.´

Finally, my own heightened sense of mortality has revealed itself as yet another gift, leading to a palpable increase in vitality as I learn to embrace it more and more. Today I welcome each new day as precious, in gratitude and wonder.

My departed loved ones, – my parents, my brother, and several wonderful close friends; they have become invisible yet radiant angels, guiding and sheltering the unfolding of my destiny. I celebrate them and give thanks, especially at this Celtic feast of Samhain.