Because of your conviction that man is something more than intellect, emotion, and two dollars worth of chemicals, you have especially endeared yourself to us.

Bill Wilson to Carl JungThe helpful formula therefore is: spiritus contra spiritum.

Carl Jung to Bill Wilson

In the last decade of his life, my now deceased brother intensified his keen interest in genealogy, taking great effort to find out who our ancestors were, where and how they lived, and where their remains were buried. Thanks to his detective work and the contributions of further siblings and cousins, we now know a little more about some of those people who have made up the narrative of our family over the centuries, helping to shape the family values and aspirations which are evident across the generations, right down to our children and our children’s children.

Some, more than others, are intrigued by our roots, the influences have shaped our lives, and how certain values and interests have established themselves across generations of people we would consider `family´. My sense of belonging is strengthened by such insights.

Our family of origin is not the only `tribe´ to which I belong. Due to the circumstances of my own life, I have come to know, to love, and become an enthusiastic member of a global `family´ of people. It is the Fellowship of recovery from addiction which originated in 1935 in Akron, Ohio, and New York City.

The first hundred members, – alcoholics experiencing the wonders of recovery, – quickly recognised that they had stumbled upon something quite novel and miraculous since, up until then, a solution to the problem of alcoholism had proved beyond human reach.

Prior to this, it was considered preordained that alcoholics would end up in one of three possible destinations: the closed psychiatric ward, the penitentiary, or an early grave. Now, living proof was emerging that, when one alcoholic reached out to help another, using a framework of self-actualisation (later formulated as the Twelve Steps) which drew upon power beyond the human ego, they both could benefit not only in terms of abstinence, but also in achieving long-term sustained sobriety, reaping the rewards of a life lived in purpose, joy, and freedom.

In 1939, these first hundred trailblazers put down on paper the framework they had discovered and how it had worked for them, in a book entitled `Alcoholics Anonymous´, now fondly known as the `Big Book´.

There was a prelude, however, to this first act of two alcoholics meeting, helping each other, and discovering the power of `the fellowship of recovery´. The two men in question were William (Bill) Wilson, an alcoholic who had managed to stay sober for six months prior to meeting Dr Bob Smith, a still-drinking alcoholic who was despairing of his condition, having wished to quit drinking for many years, only to fail repeatedly. When they met, the seed of Alcoholics Anonymous germinated. They never looked back, remained sober themselves, continued to carry the message, and witnessed thousands of successful recoveries among the first generations of the fellowship they had spawned.

The prelude began in the 1920s, in the consultation rooms of a Swiss psychiatrist of international renown, Carl Gustav Jung, at his home in Küsnacht, a suburb of Zürich. The client who had sought out Dr Jung was a young male member of a wealthy American industrialist family, the Hazards, from Rhode Island. Rowland Hazard III was, by all accounts, both intelligent and empathetic, and, after graduating from Yale, was destined to continue the commercial success of his dynasty, but for the fact that, by early middle life, he found himself in the throes of full-blown alcoholism.

He had already sought out help from leading lights in the medical field in North America, alas to no avail, before travelling to Europe to consult with Dr Jung. Though there are no records in the public domain to be drawn upon, it appears that they met weekly for several months, with Dr Jung attempting to bring about a psychic shift in his client, using the plentiful resources at his disposal, many of which he had himself developed.

At the end of this seemingly successful treatment, Rowland Hazard, now several months dry, was confident that he could remain abstinent and return to the US to continue his recovery. He only got as far as Paris, however, where someone asked him the wrong question: `Would you like a glass of champagne, Sir?´

Returning to Zurich with his tail between his legs, distraught and depressed, he once again sought out Dr Jung. He asked him what hope, if any, there was for him. Jung was frank with his American client.

According to the account set out in Chapter 2 of the Big Book of AA – `There Is a Solution´, Jung pronounced Rowland Hazard a chronic alcoholic and therefore hopeless. In Jung’s estimation, he was beyond the reach of human medicine as far as it had been developed at that time. Jung cited as proof, his own inability — despite his best efforts, — to bring about the psychic or spiritual change in Hazard, which he considered to be the prerequisite of recovery from such a malady as his.

Jung considered such a phenomenon, — the life-changing `vital spiritual experience´ — essential for recovery from the craving of the alcoholic. It could be observed but not explained. Jung further advised that Rowland’s affiliation with a church was insufficient for this purpose, as it did not equate to the necessary `vital experience´.

This prognosis so shook Rowland that he sought out the Oxford Group, an Evangelical Christian movement prominent in the first half of the twentieth century. The Oxford Group was dedicated to what its members termed `The Four Absolutes´ (taken from the Sermon on the Mount): absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute unselfishness, and absolute love. The Group was also dedicated to the vigorous pursuit of personal change, and to extending the message of hope through change by means of `personal evangelism´, i.e., one changed person sharing his experience with another.

Rowland was already very familiar with the Oxford Group’s emphasis on personal evangelism when, in 1934, he came in contact with an alcoholic named Ebby Thatcher while summering in Vermont with two other Oxford Group members who knew Thacher. Thacher was the son of a prominent New York family who, like many well-to-do Eastern US families of the period, summered in New England, forming lifelong associations and friendships with other `summer people´ as well as with residents.

Upon learning that, on account of his drinking, Ebby was facing commitment to the Brattleboro Retreat (the former Vermont Asylum for the Insane), Rowland and fellow Oxford Group members Shep Cornell and Cebra Graves sought out Ebby and shared with him their Oxford Group recovery experiences.

Graves was the son of the family court magistrate in Ebby’s case, Collins Graves, and the Oxford Groupers were able to arrange for Ebby’s release into their care. This led to Ebby’s move to New York City, his acceptance of the principles of the Oxford Group, and his own first experience of sobriety. Encouraged by the example of personal evangelism from which he had benefitted, Ebby later sought out an acquaintance of his own, then also living in New York.

This was Bill Wilson, another hopeless (active) alcoholic. An old childhood friend of Ebby’s (they had spent their summers together in Vermont), at that time Bill was a washed-up, once successful Wall Street Broker, on death’s doorstep due to the advanced stage of his alcoholism. Though sceptical of the story the now-sober Ebby related to him during this initial encounter, he was sufficiently piqued to seek out the help of the Oxford Group at a later point in time.

Bill did eventually get sober in late 1934. Six months in, in June 1935, he met and befriended Robert (Bob) Smith while on a business trip in Akron. They engaged in a process of mutual support which turned out to be very effective, whereupon the fellowship of AA was born.

Some 25 years later, Bill Wilson wrote to Carl Jung to express his gratitude and appreciation for his contribution to the formation of the now-thriving international AA movement. The letter reads as follows:

January 24, 1961

My dear Dr Jung,

This letter of great appreciation has been very long overdue.

Many I first introduce myself as Bill W., a co-founder of the Society of Alcoholics Anonymous. Though you have surely heard of us, I doubt if you are aware that a certain conversation you once had with one of your patients, a Mr. Rowland H., back in the early 1930s, did play a critical role in the founding of our fellowship.

Though Rowland H. has long since passed away, the recollections of his remarkable experience while under treatment by you has definitely become part of AA history. Our remembrance of Rowland H.’s statement about his experience with you is as follows:

Having exhausted other means of recovery from his alcoholism, it was about 1931 that he became your patient, I believe he remained under your care for perhaps a year. His admiration for you is boundless, and he left you with a feeling of much confidence.

To his great consternation, he soon relapsed into intoxication. Certain that you were his `court of last resort´, he again returned to your care. Then followed the conversation between you that was to become the first link in the chain of events that led to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

My recollection of his account of that conversation is this: First of all, you frankly told him of his hopelessness, so far as any further medical or psychiatric treatment might be concerned. This candid and humble statement of yours was beyond doubt the first foundation stone upon which our Society has since been built.

Coming from you, one he so trusted and admired, the impact upon him was immense.

When he then asked you if there was any other hope, you told him that there might be, provided he could become the subject of a spiritual or religious experience — in short, a genuine conversion. You pointed out how such an experience, if brought about, might remotivate him when nothing else could. But you did caution, though, that while such experiences had sometimes brought recovery to alcoholics, they were, nevertheless, comparatively rare. You recommended that he place himself in a religious atmosphere and hope for the best. This I believe was the substance of your advice.

Shortly thereafter, Mr. H. joined the Oxford Group, an evangelical movement then at the height of its success in Europe, and one with which you are doubtless familiar. You will remember their large emphasis upon the principles of self-survey, confession, restitution, and the giving of oneself in service to others. They strongly stressed meditation and prayer. In these surroundings, Rowland H. did find a conversion experience that released him for the time being from his compulsion to drink.

Returning to New York, he became very active with the `O.G.´ here, then led by an Episcopal clergyman, Dr Samuel Shoemaker. Dr Shoemaker had been one of the founders of that movement, and his was a powerful personality that carried immense sincerity and conviction.

At this time (1932-34) the Oxford Group had already sobered a number of alcoholics, and Rowland, feeling that he could especially identify with these sufferers, addressed himself to the help of still others.

One of these chanced to be an old schoolmate of mine, Edwin T. (Ebby). He had been threatened with commitment to an institution, but Mr. H and another ex-alcoholic `O.G.´ member procured his parole and helped to bring about his sobriety.

Meanwhile, I had run the course of alcoholism and was threatened with commitment myself. Fortunately, I had fallen under the care of a physician — a Dr William D. Silkworth — who was wonderfully capable of understanding alcoholics. But just as you had given up on Rowland, so had he given me up. It was his theory that alcoholism had two components — an obsession that compelled the sufferer to drink against his will and interest, and some sort of metabolism difficulty which he then called an allergy. The alcoholic’s compulsion guaranteed that the alcoholic’s drinking would go on, and the allergy made sure that the sufferer would finally deteriorate, go insane, or die. Through I had been one of the few he had thought it possible to help, he was finally obliged to tell me of my hopelessness. I too, would have to be locked up. To me, this was a shattering blow. Just as Rowland had been made ready for his conversion experience by you, so had my wonderful friend, Dr Silkworth, prepared me.

Hearing of my plight, my friend Edwin T. came to see me at my home where I was drinking. By then, it was November 1934. I had long marked my friend Edwin for a hopeless case. Yet there he was in a very evident state of `release,´ which could by no means be accounted for by his mere association for a very short time with the Oxford Group. Yet this obvious state of release, as distinguished from the usual depression, was tremendously convincing. Because he was a kindred sufferer, he could unquestionably communicate with me at great depth. I knew at once I must find an experience like his, or die.

Again, I returned to Dr Silkworth’s care, where I could be once more sobered and so gain a clearer view of my friend’s experience of release, and of Rowland H.’s approach to him.

Clear once more of alcohol, I found myself terribly depressed. This seemed to be caused by my inability to gain the slightest faith. Edwin T. again visited me and repeated the simple Oxford Group’s formulas. Soon after he left me, I became even more depressed. In utter despair I cried out, `If there be a God, will He show Himself.´ There immediately came to me an illumination of enormous impact and dimension, something which I have since tried to describe in the book `Alcoholics Anonymous´ and in `AA Comes of Age,´ basic texts which I am sending you.

My release from the alcohol obsession was immediate. At once I knew I was a free man.

Shortly following my experience, my friend Edwin came to the hospital, bringing me a copy of William James’ `Varieties of Religious Experience.´ The book gave me the realization that most conversion experiences, whatever their variety, do have a common denominator of ego collapse at depth. The individual faces an impossible dilemma. In my case the dilemma had been created by my compulsive drinking, and the deep feeling of hopelessness had been vastly deepened by my doctor. It was deepened still more by my alcoholic friend when he acquainted me with your verdict of hopelessness respecting Rowland H.

In the wake of my spiritual experience there came a vision of a society of alcoholics, each identifying with and transmitting his experience to the next — chain style. If each sufferer were to carry the news of the scientific hopelessness of alcoholism to each new prospect, he might be able to lay every newcomer wide open to a transforming spiritual experience. This concept proved to be the foundation of such success as Alcoholics Anonymous has since achieved. This has made conversion experiences — nearly every variety reported by James — available on an almost wholesale basis. Our sustained recoveries over the last quarter-century number about 300,000. In America and through the world, there are today 8,000 AA groups.

So to you, to Dr Shoemaker of the Oxford Group, to William James, and to my physician, Dr Silkworth, we of AA owe this tremendous benefaction. As you will now clearly see, this astonishing chain of events actually started long ago in your consulting room, and it was directly founded upon your own humility and deep perception.

Very many thoughtful AAs are students of your writings. Because of your conviction that man is something more than intellect, emotion, and two dollars worth of chemicals, you have especially endeared yourself to us.

How our Society grew, developed its Traditions for unity, and structured its functioning will be seen in the texts and pamphlet material that I am sending you.

You will also be interested to learn that in addition to the `spiritual experience,´ many AAs report a great variety of psychic phenomena, the cumulative weight of which is very considerable. Other members have — following their recovery in AA — been much helped by your practitioners. A few have been intrigued by the `I Ching´ and your remarkable introduction to that work.

Please be certain that your place in the affection, and in the history of the Fellowship, is like no other.

Gratefully yours,

William G. W.

Carl Jung, who was to die, aged 85, less than six months later, replied immediately in his own graceful style:

January 30, 1961

Dear Mr. Wilson,

Your letter has been very welcome indeed.

I had no news from Roland (sic) H. anymore and often wondered what has been his fate. Our conversation which he had adequately reported to you had an aspect which he did not know. The reason, that I could not tell everything, was that those days I had to be exceedingly careful of what I said. I had found out that I was misunderstood in every possible way. Thus, I was very careful when I talked to Roland H. But what I really thought about, was the result of many experiences with men of his kind.

His craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God*.

How could one formulate such an insight in a language that is not misunderstood in our days?

The only right and legitimate way to such an experience is, that it happens to you in reality and it can only happen to you when you walk on a path, which leads you to a higher understanding. You might be led to that goal by an act of grace or through a personal and honest contact with friends, or through a higher education of the mind beyond the confines of mere rationalism. I see from your letter that Roland H. has chosen the second way, which was, under the circumstances, obviously the best one.

I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world, leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition, if it is not counteracted either by a real religious insight or the protective wall of human community. An ordinary man, not protected by an action from above and isolated in society cannot resist the power of evil, which is called very aptly the Devil. But the use of such words arouses so many mistakes that one can only keep aloof from them as much as possible.

These are the reasons why I could not give a full and sufficient explanation to Roland H. but I am risking it with you because I conclude from your very decent and honest letter, that you have acquired a point of view above the misleading platitudes one usually hears about alcoholism.

You see, Alcohol in Latin is spiritus, and you use the same word for the highest religious experience as well as for the most depraving poison. The helpful formula therefore is: spiritus contra spiritum.

Thanking you again for your kind letter, I remain,

Yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung

* As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after Thee, O God.´ Psalm 42,1

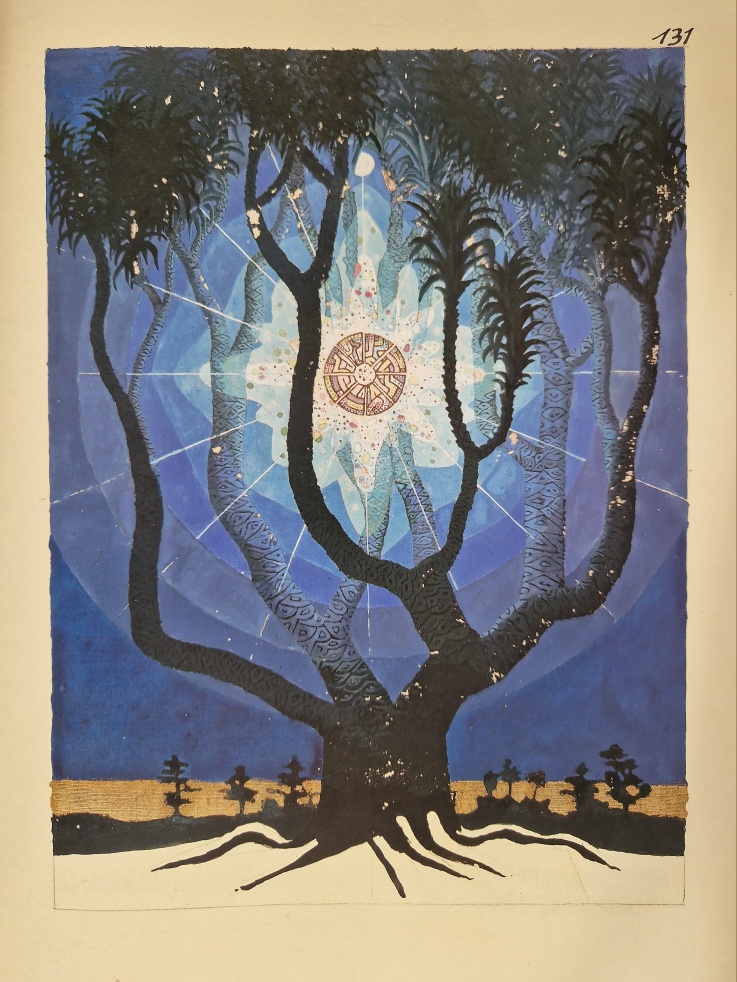

Artwork: C G Jung, The Red Book