People who suffer from alexithymia tend to feel physically uncomfortable but cannot describe exactly what the problem is. As a result, they often have multiple vague and distressing physical complaints that doctors can’t diagnose. In addition, they can’t figure out for themselves what they’re really feeling about any given situation or what makes them feel better or worse.

This is the result of numbing, which keeps them from anticipating and responding to the ordinary demands of their bodies in quiet, mindful ways. If you are not aware of what your body needs, you can’t take care of it. If you don’t feel hunger, you can’t nourish yourself. If you mistake anxiety for hunger, you may eat too much. And if you can’t feel when you’re satiated, you’ll keep eating.

Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score

I grew up in a family that taught me how not to feel.

Shared at a recent Twelve Step meeting

The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain. Is not the cup that holds your wine the very cup that was burned in the potter’s oven? And is not the lute that soothes your spirit, the very wood that was hollowed with knives? When you are joyous, look deep into your heart and you shall find it is only that which has given you sorrow that is giving you joy. When you are sorrowful look again in your heart, and you shall see in truth that you are weeping for that which has been your delight.

Kahlil Gibran

Resilience isn’t really about returning back to the way you were before but is much more about reclaiming whatever new shape your form has taken. A resilience that doesn’t really ask us to forget, but that carries the memory of whatever harm or whatever fire we’ve been through.

Cole Arthur Riley

Years ago, when my children were very young, I spent two early pre-work hours each Wednesday with a Jungian psychotherapist. As the 29-year-old father of two, challenged by married life, burdened with the financial responsibility for our young family, and compelled to prove myself in the world, I felt overwhelmed and sought help, in the hope of developing better coping skills.

In retrospect, this therapy was helpful in keeping me afloat during that challenging period. The fact that my substance addiction never made it onto the agenda a reflection, in equal parts, of the denial and acting skills of the client (me) and the widespread ignorance, with respect to addiction, trauma, and psychosomatic dis-ease, still prevalent even today among mental health professionals.

I do have much gratitude toward this therapist and some fond memories of our encounters. One morning, on hearing: `How are you today?´, I drew a blank and frankly said so. For some reason, my guard was down, and it felt good to tell it like it was.

He didn’t miss a beat as he explored further. He asked me how my body felt. Any tightness, palpitations, or unusual sensations? Again, nothing. We sat in silence for some time, the summer birdsong drifting in through the inclined windows, from the garden below.

`Mr. Little, would you be willing to try out something new?´ were the next words spoken. `Sure´, I said, eager to break the impasse.

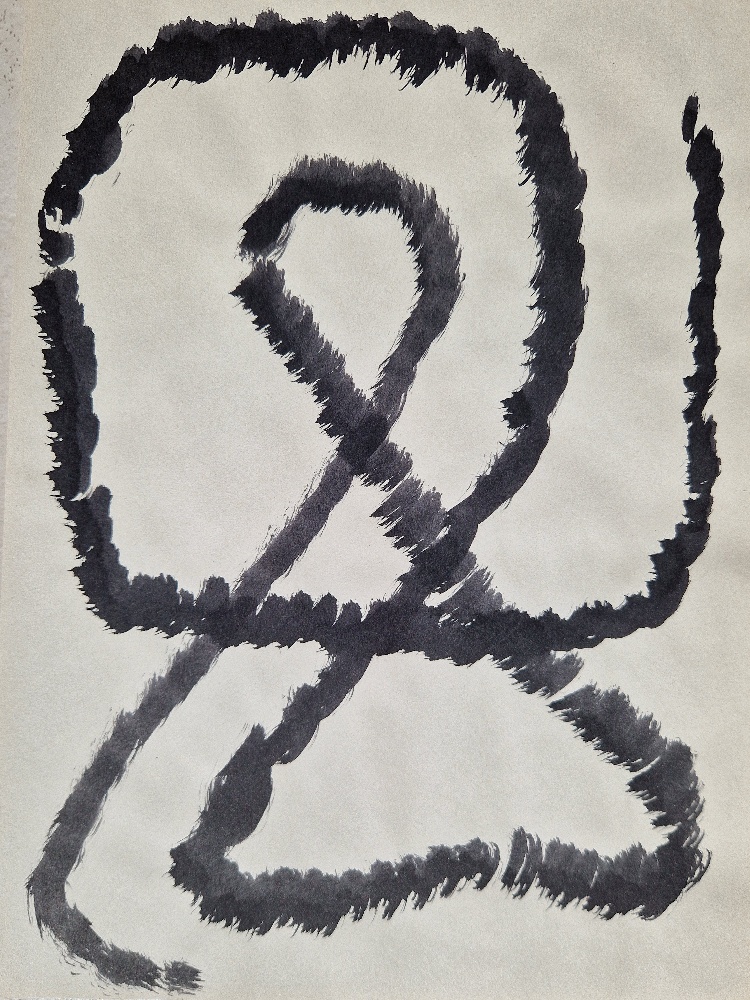

`I want you to purchase a bottle of ink and a little brush. You will also need a block of white paper sheets. Each day, preferably at the same time set aside for this exercise, please dip the brush in the ink and then draw it along the page until the brush has become dry. No preparation or analysis required; just follow your intuition. Then bring the pages into next week’s session and we can review them together.´

Eager to get the best out of these therapy sessions, on the following Wednesday I arrived with six sheets of paper, each with an example of my unbroken, winding scrawling.

Pleased with the bounty laid out on the table before him, he asked me to pick one and then describe it. Before I realised it, he had taken me a level deeper, asking me about what was on the page and how I had felt during the creative process, always with reference to how these feelings manifested in my body. As I became more engaged, he began, slowly but surely, to assist me in turning the key in the safe door behind which many of my more nuanced feelings had been hidden for so long.

An aside worthy of mention here was his intervention to help delineate between feelings and beliefs. When at one point I said `I feel neglected´, he feigned astonishment and asked me to show him where I felt this in my body. I couldn’t, of course, because `neglect´ is not a feeling.

He explained that when we believe we are being neglected, there is usually an array of feelings just underneath. Only when we begin to penetrate the shield of limiting beliefs can we identify feelings and feel them as they move through our body. That’s when we can experience, embrace, and befriend the emotions that are truly at play.

The term alexithymia (from the Greek a = lack, lexis = word, thymos = emotion) was first coined by the Greek/US psychiatrist Peter E. Sifneos in 1972 after noticing that some patients showed extreme difficulties in talking about their emotions, as in the case described above.

Dr Sifneos introduced the term alexithymia to describe the marked difficulty in experiencing, identifying, differentiating, and expressing feelings; as well as a hyper-rational way of thinking and interacting.

Individuals with alexithymia may have difficulty in recognizing emotional states as they are happening and may also struggle to recognize and respond to emotions in others. They seem to be bereft of the language to describe (to themselves and others) the emotions they are experiencing.

Many psychiatric challenges overlap with alexithymia. For example, there is increased incidence of alexithymia among war veterans who have suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

What is true of PTSD is equally true of Complex PTSD, or Developmental Trauma, the regular exposure to alienation, abandonment, anxiety, high vulnerability, and the state of feeling overwhelmed, which many of us have experienced in childhood.

The inability to modulate emotions may explain why some people with alexithymia are prone to discharge tension arising from unpleasant emotional states through impulsive behaviours, – rage, drama, self-pity, etc., – or compulsive habits such as overeating, substance abuse, workaholism, porn consumption, screen addiction, or any of the myriad forms of addiction prevalent in our culture today.

Dr Sifneos postulated that people with alexithymia show a limited ability to experience the entire range of emotions: they are often not only unable to consciously experience feelings of distress but any feelings at all, including joy, wonder, and pleasure.

Over the years I have developed compassion for the child within who adopted the strategy of not feeling at all, or at least trying to feel only self-induced states such as those generated by childhood daydreaming and, later, draining a few bottles and/or smoking joints.

Even these sensations wear out over time, resulting in a more intense state of stupor. For those who live in the fear of fear of their own emotions, stupor appears to be the better option. Until it is revealed as the Grim Reaper in disguise.

Being sick and tired of being sick and tired propelled me to seek help in rediscovering and rebooting my `Yes!´ to life, which, by then, had gone missing. That help was readily available in several different Twelve Step recovery communities.

Living in recovery since 2003 has been a journey of discovering life on life’s terms and learning to live accordingly. Along the way, it became clear why not feeling my feelings seemed the preferable option. Childhood was, at times, an unbearable experience for me, – almost.

Recovery provides us a second chance to revisit that apparent unbearability of being, and to process that experience with the help of the recovery community and the many resources we have accumulated since we were five years old.

It is not a process without pain. But if we’re willing to feel and participate in the pain of the world, a part of us will experience a kind of despair which fully opens our hearts. Emotions are then allowed to run their course. We recognise that they are neither right nor wrong; they are merely indicators of what is happening, important signposts along the way.

The difference is that now we can bear that burden of pain and grow through the experience. The Inner Child which I, myself, had ignored and discounted for so many years, has become a good friend. He has begun to trust and engage with the adult Patrick and vice versa.

In this new relationship, anything may now bubble to the surface, uncensored, and be given space and attention, until it dissipates. Much pain, sadness, and grief has emerged over the years, leaving me lighter over time. My capacity for real joy, wonder, and gratitude has increased accordingly.

In the Positive Intelligence (PQ) Mental Fitness modality which I now often use in my work as a Transformation Coach, the main universal Saboteur is the Judge, aka the `Inner Critic´. The Judge is relentless in his criticism of self, others, and circumstances. According to him, we are never good enough and life is always going to be a struggle.

This Saboteur is assisted by a band of further fear-driven Saboteurs, their relative strengths reflecting how we each evolved through childhood. Some have pronounced Pleaser, Controller, Victim, or Hyper-Vigilant Saboteurs, just to mention a few.

In my case, the main accomplice Saboteur is the Hyper-Rational. This one says that emotions are too messy and need to be taken out of the equation of human interaction altogether. Its justification lie is: The rational mind is the most important thing. It should be protected from the wasteful intrusion of people’s messy emotions and needs, so it can get its work done.

Its original survival strategy was intelligent, appropriate, adaptive, perhaps even inevitable, in the given circumstances of emotional turmoil, attachment dysfunction, intellectualism, religious harshness, and chaos.

The escape into the neat and orderly rational mind generates a sense of security and, perhaps, a sense of intellectual superiority. It provided the only stability available to me, the overwhelmed child.

By showing up as the smartest person in the room, it also gained me attention and praise. For the traumatised child, attention of any kind is better than none.

Unfortunately, like all Saboteurs, the Hyper-Rational produces exactly the opposite of the intended effect. Instead of safety, we experience increasing isolation. Longing never ripens into belonging.

We continue to be as baffled by life as we were in childhood. That state of feeling overwhelmed and out of place persists. This is all grist on the mill of the Judge’s favourite game, which we can never win. It is called: `I’ll be happy when…´.

PQ has become an integral part of my life. Through a regime of daily body-based exercises, we learn to intercept the Saboteurs before they can kick into action and shift to the Sage Powers of Empathy, Explore, Navigate, Innovate, and Activate. We realise that happiness is an inside job and are given the necessary tools and practices to do the inner work.

Alexithymia can be addressed and overcome by applying the Powers of Sage. Mental Fitness, just like physical fitness, is made up of 20% insight and 80% regular practice. Practice makes progress, one day at a time.

With increased mental fitness, we can consciously partake of the world, now a haven of compassion and belonging. We shift from standing `apart from´ to being `a part of´ life.

Emotional sobriety is not about feeling better all the time; it’s about getting better at feeling. When this happens, and we learn how to handle those feelings with awareness and loving kindness, we become emotionally reawakened, attuned, and revivified. Our zest for life returns.