Autonomy is the drive to be an active agent in your life, to govern yourself, and to shape the direction and organisation of your life.

Dr. Maureen Gaffney: `Your One Wild and Precious Life´

Autonomy: The urge to direct our own lives. Mastery: the desire to get better and better at something that matters. Purpose: the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves. These are the building blocks of an entirely new operating system for our businesses.

Daniel H. Pink

Each group should be autonomous except in matters affecting other groups or A.A. as a whole.

The Twelve Traditions of A.A. – Tradition Four

In her recent book, Maureen Gaffney points out that we are all born with three innate drives; the need for close connection with other people, the need for autonomy, and the need for competence. She describes these drives as `the big engines of personal development at every life stage and the non-negotiable requirements for a happy, fulfilled, and successful life´.

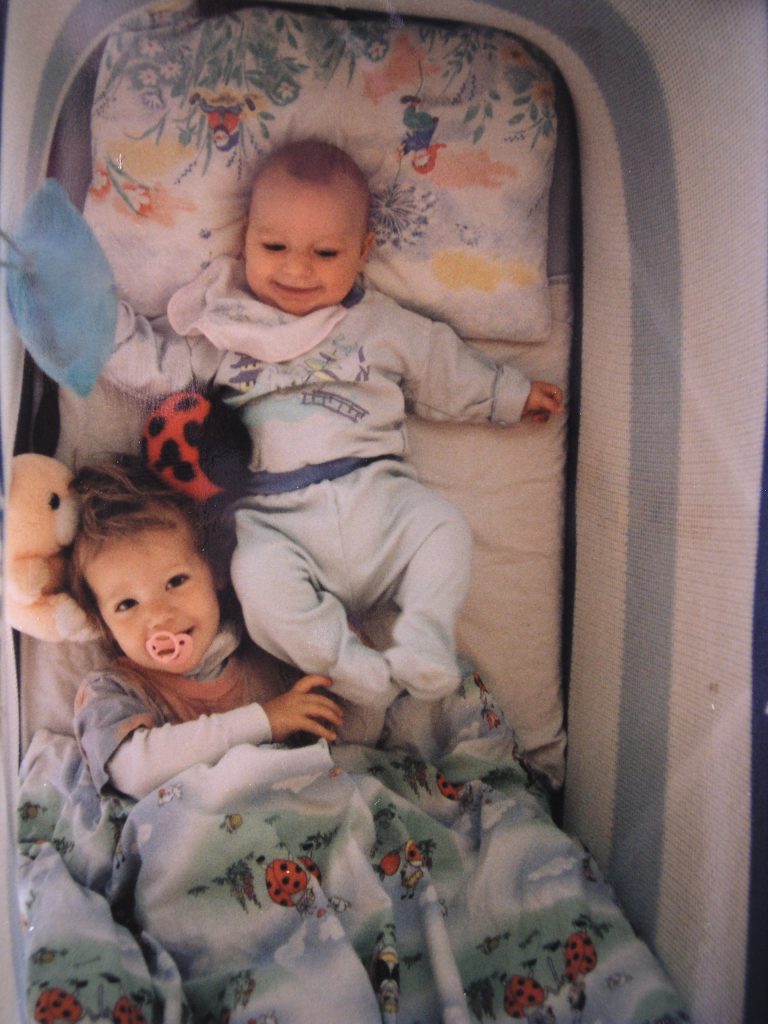

We humans are, at birth, the most vulnerable of mammals. Whereas the foal will spring up and walk around directly after birth, we humans need almost a full year to even begin to learn how to walk upright. This is just one example. Our initial helplessness and absolute need of protection and nurturing is one of the things that differentiates us from our mammal cousins. It requires of us, as parents and carers, to expend great time, energy, and loving-care, to meet the needs and ensure the survival of our offspring in the early phases of childhood.

Yet, after the first few years, our children show a distinct tendency and desire to `do things themselves´. This is the emergence of the autonomy drive, which usually reaches its zenith in our teen years and the third decade of our lives. It is part and parcel of the maturing process from childhood to adulthood.

How, and how early, this drive manifests is determined by our unique personality and the environment in which we grow up. Blessed with a somewhat headstrong personality and born as the fifth of ten children, my autonomy drive was substantially shaped by my experiences in my family of origin. Many have an idyllic notion of growing up in a large family. My experience was a mixed bag. There is, to this day, a great centrifugal force operating on our family. This brings precious blessings such as deep bonds, solidarity and lots of action and fun.

As a child, my day-to-day life was also characterised by competition, chaos, stimulus overload, and the pressure to be highly functional. This final area is one in which I excelled. Constantly on the lookout for ways to alleviate the atmosphere of overwhelming chaos, I quickly developed competences in workflow management and process engineering. By the age of fourteen, I could single-handedly cook the Sunday dinner while everybody else was out at mass. This garnered me accolades and I could do it my way.

This was another main issue. I have a very particular idea of how things should look, taste, and feel. My early experience was that often, when others tidied up a room, cooked a meal, or bought furniture, the results were not to my satisfaction. So, in order to secure my satisfaction, I was often driven to learn to do these things myself. This is how my drive for autonomy grew strong right from the beginning.

So far so good. Now add a few ingredients such as unprocessed grief and trauma, obstinacy, defiance, pride, hubris, as well as an underlying sense of insecurity, despite high levels of competence and autonomy, and we have a recipe for trouble. There were real causes for grief and trauma, so these do not now incur my judgement but rather empathy and understanding.

I dropped out of university because `I knew everything´ and was in an awful hurry to escape the restraining societal and family efforts to determine my course in life. Having emigrated to Germany at the age of twenty, I had the freedom and anonymity to plough my own furrow.

I also liked to party. Drink and other drugs took the edge off the intolerability of my frequent states of `restlessness, irritability, and discontentedness´. I escaped Ireland, only to soon discover that I had taken myself with me. On the one hand, my autonomy drive paved the way to earning a good living while progressing through several phases of `learning on the job´ in interesting professions. On the other hand, as my problems kept piling up, I remained convinced that `I had to solve them myself´. Reaching out for help was not a tool in my shed. The inevitable crash came in my early forties; seeking help was no longer merely an option, but became a necessity. Once I got clean and sober and began to participate in Twelve Step fellowships for all manner of addictions, things began to improve. It is a work in progress to this day.

Recovery is often described as a process of right-sizing the ego. In admitting our powerlessness over our addictions, the old ideas concerning autonomy (my way!) are exposed as illusory. We gradually recognise that, while we act out our lives, we are not the director. The script is written elsewhere; ours is the task of making the best of the cards we are dealt. The result is the humility of living `life on life’s terms’ rather than the old pattern of insisting on `life on Patrick’s terms´. There ensues a form of shared autonomy of sorts, that between the egoic self and the divine Self within; accepting the things we cannot change, changing the things we can, growing in the wisdom to know the difference, and trusting in the guidance and protection of the Great Spirit for all matters beyond my control. This autonomy need always be tempered by the needs of the wider community and the higher good; alignment with my inner values, however, is always the final litmus test.

Over Christmas, I was preparing to go to an orthopaedic rehab clinic for four weeks treatment to boost my recovery from an accident in the summer which had resulted in serious spinal injuries. As the departure date approached, thoughts of food, daily schedule, surroundings, etc. began to cross my mind. It slowly dawned on me, that I would have to relinquish my autonomy in all of these areas, and more, while at the clinic. It was going to be a challenging exercise in leaving my comfort zone.

Upon arrival, it took me three or four days to come to terms with my new situation. Once I could identify and let go of my unconscious insistence of getting the clinic to operate `my way´, I began to relax. Indeed, many of the patients here appear to be engaged in a similar conflict. The loss of autonomy, because not only of being away from home, but also due to injury, restricted mobility, and senescent frailty, is written into the body language of many of my co-patients and reverberates in many of the conversations between them.

For me, it is a good lesson in acceptance. Acceptance of the life cycle which sees us extremely vulnerable and bereft of autonomy at birth, growing in egoic autonomy throughout the early decades, which may or may not be superseded by shared autonomy once we pass the mid-life milestone, only to be finally fully relinquished, at the very latest, when our soul leaves this earthly body.

For, as Antony Hopkins once astutely observed: `None of us are getting out of here alive´! Until my time comes, I hope to continue to cultivate the state of shared autonomy I have gained in recovery. To this end, I look forward to making the best of this opportunity to fortify my body and encourage my fellow patients in their autonomy, during my remaining ten days here in rehab.