All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Leo Tolstoy

If you think you’re enlightened, go spend a week with your family.

Ram Das

When you look into that mirror, you’ll see both Mum and Dad.

Eoin Little

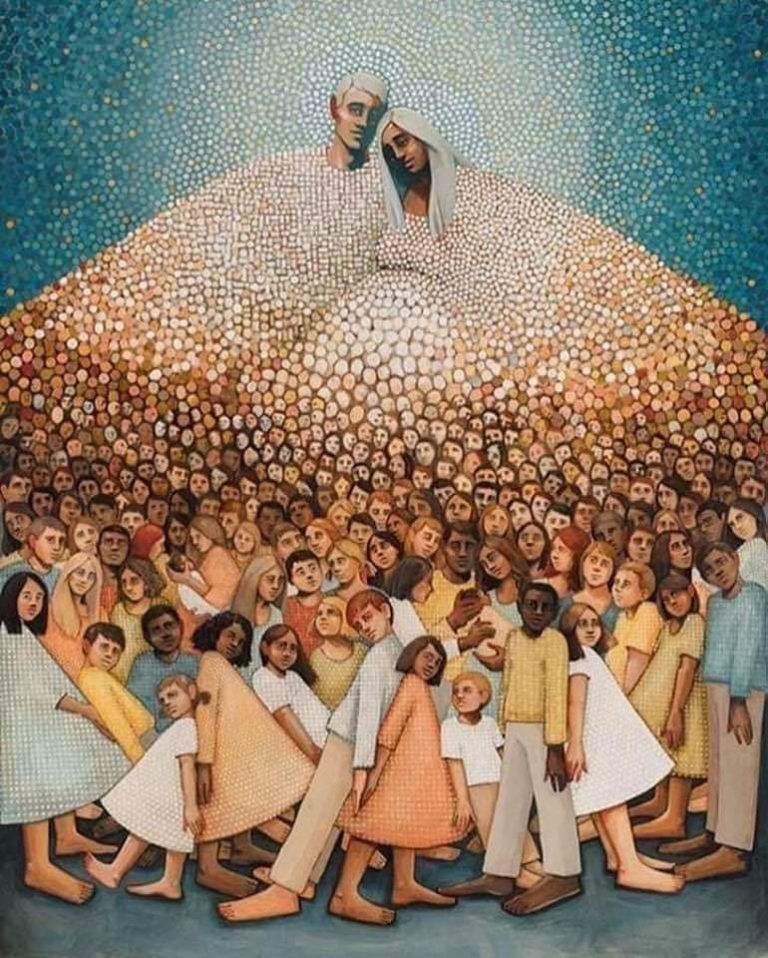

For us to incarnate we need: 2 parents, 4 grandparents, 8 great-grandparents, 16 great-great-grandparents, 32 great-great-great-grandparents, 64 penta-grandparents, 128 hexa-grandparents, 256 hepta-grandparents, 512 octa-grandparents, 1024 enea-grandparents, and 2048 deca-grandparents.

The sum of those ancestors over eleven generations is 4,096; all of them lived within the space of roughly three hundred years up to the time of our birth.

These days, we often here the statement: `It’s in her or his DNA.´ What do we mean by that? Let’s first consider the relatively-recently formulated scientific perspective.

DNA was first isolated by the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher in 1869. In 1937, the first X-ray diffraction patterns showed that DNA had a regular structure. DNA’s role in heredity was confirmed in 1952 when Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase showed that DNA is the genetic material of a virus called enterobacteria phage T2. In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize for their work on DNA and their role in founding what is today called molecular biology.

Molecular biology has taught us that genes are made from a long molecule called DNA, which is copied and inherited across generations. DNA is made of simple units that line up in a particular order within this large molecule. The order of these units carries genetic information, like how the order of letters on a page carries information. The language used by DNA is called the genetic code, which lets organisms read the information in the genes. This information comprises the instructions for constructing and operating a living organism.

Genes are inherited as units, with two parents dividing out copies of their genes to their offspring. Humans have two copies of each of their genes, but each egg or sperm cell only gets one of those copies for each gene. An egg and sperm join to form a complete set of genes. The resulting offspring has the same number of genes as their parents, but for any gene, one of their two copies comes from their father, and one from their mother.

So far, so good. Deconstructed in this manner, we can see that each of us is a genetic distillation of those 4,094 ancestors over the most recent eleven generations and the countless generations that preceded them. As Darwin showed, also very recently, nature has an in-built intelligence to enhance the survival probability of each new generation by incorporating lessons that each new generation learns or, indeed, doesn’t learn.

From a more general perspective, let me tell you of an interaction I had recently with a man who had turned his back on a purely urban existence and, having joined a farming community, had begun his first garden in his late thirties. Though his garden was already fabulous, he was troubled by his lack of experience. `I don’t know how to do this. I really haven’t a clue´, he remonstrated with himself. Reflecting on my own experience, I said: `Fabrizio, you do know how to do it; you just don’t yet know that you know.´ I went on to explain that our ancestors, both his and mine, had been living off the land for centuries and that the knowledge was encoded and deeply etched in our being. It was simply a matter of tapping into that knowledge, or intuition, and trusting that it would lead us to the desired results. We both felt better after this conversation.

Widening this lens, the work of pioneers such as Carl Gustav Jung and Joseph Campbell tells us that the consciousness of all of humankind is `collective´, i.e., we share the same memories, impressions, and even traumas, which have been part of the human condition since the first apes began to move upright across the savannahs.

One aspect of Jung’s pioneering work, backed up by the most recent discoveries in neurology, could now be described using a modern analogy; our `minds´ are not only stored in our physical brains, but are also encompassed in the `cloud´ of the sum of collective consciousness which has been forming since the dawn of time. This could explain such phenomena as déjà vu, synchronicity, and telepathy.

Campbell, in his eight decades of work on myths and mythology, demonstrated that disparate cultures, which never had direct contact with each other, have the same fundamental legends and myths, such as the Hero’s Journey. Again, the concept that every human being who has ever lived has had access this `cloud´, regardless of geography or time, would explain how this has come about. Each new generation refines the content of this `cloud´, which then informs the consciousness of the next.

Zooming even further back before the advent of homo sapiens, right back to the origins of life in the Universe as we know it today, we can extend the contention of collectivity to the point that we are all one with Creation. This perspective, beautifully expressed in the term `atonement´, it that of the Buddhist philosophy and the teachings of the great Mystics throughout the ages.

`When you feed the hungry, you feed me´, Christ said to his bewildered listeners. In Matthew 25:40 we read: `The King will reply, `Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.´´ If we applied this principle to the current challenges of our species, we would end the practice of war, of the killing sentient beings to satisfy our appetites, and would treat our Blue Planet in a manner which would ensure the sustenance of life into the coming millennia.

On of the great strokes of luck in my life has been to incarnate as the fifth of ten siblings in a family structure more traditional in earlier generations of Irish Catholics. Growing up in the loud, chaotic order of this family was not easy for me. In fact, one of the main reasons I put 2,000 km between myself and the place I grew up, was to get away from my family. That was forty years ago.

Much has changed in the meantime. This microcosm of Creation is now one of my greatest gifts. When we do gather for special occasions, as has been the case recently, what we have in common is much more evident than that which sets us apart. There is much laughter, loving-kindness, and empathy for each other. Our deceased parents would certainly find it heart-warming.

And when each of us looks into that mirror, we do see both Mum and Dad; in that respect we are the same, yet we are each very different in our own unique day.

Artwork: Caitlin Connolly