The first step that the earnest student must take to locate the Inner Light within herself is to settle on a definite method of working, selecting whichever one seems to suit her best, and then giving it a fair trial. Merely reading books, making good resolutions, or talking plausibly about the thing will get her nowhere.

Emmet Fox

As traumatized children, we always dreamed that someone would come and save us. We never dreamed that it would, in fact, be ourselves as adults.

Alice Little

Children don’t get traumatized because they are hurt. They get traumatized because they’re alone with the hurt.

Dr. Gabor Maté

People start to heal the moment they feel heard.

Cheryl Richardson

My life could be broken down into various phases which include childhood adversity, addiction recovery, healing, and growing in emotional sobriety. In the process, it has been necessary to re-encounter the pain of the early experiences of adversity, which had cast long shadows into adulthood. I then moved into the work of subsequently addressing and resolving them.

This is a multi-stage process. It involves soothing the Wounded Inner Child (`I feel sad´), accepting and containing the internalised reactions of the overwhelmed Adopted Adult Child (`Pull yourself together!´), and moving on in the healed energy of the Functional Adult (`In gratitude, I can both carry the pain of the past and share the gifts of what it has brought me.´).*

The following example is drawn from personal experience.

It was a dank October afternoon, the light already beginning to fade before the clock struck five, when I returned home on my bike from a long day at school. For the duration of my cycle the incessant Irish rain had threatened, but thankfully held off. However, the blustery crosswind blowing up from the estuary had a nasty chill to it, so I was looking forward to getting a warm cup of tea upon arrival, before checking in with Dad. These were the thoughts which were spinning through my mind as I pedalled home. Then, having surmounted the final crest onto O’Connell Avenue, I began to roll down the incline to my destination, when I looked up and had a rude awakening.

On the thoroughfare directly in front of our garden gate stood an ambulance. Frightening thoughts shot through my mind. He had been fine when I last saw him after breakfast, when I looked in on him on my way out to school. What might have transpired during the day that would require the attendance of medics? I hurriedly completed the final hundred yards of my cycle, just in time to witness him being carried on a stretcher through the gate. I jumped off my bike as he was being placed in the back of the ambulance. Our eyes met. His, – weary, perhaps accusatory; mine, – surprised, aghast, and angry. What the hell is going on?

In the spring before my sixteenth birthday my father had fallen ill. He was diagnosed with lung cancer and had surgery to remove most of his right lung. In those days – (the mid-1970’s), the prognosis for such patients was not very good, but his medical colleagues gave him `from one to thirty years´. He didn’t make the one. In the summer and early autumn months of that year, I spent much of the time with him, as he set out on his final journey.

It was during these months that I first made the acquaintance of death and dying. I had little or no grasp of what was going on, yet knew intuitively that, as the oldest boy at home, I had an important role to play in this process. My four older siblings were already off at school or college. It fell to me to accompany him on this journey and, – as his appointed emissary who would convey his dreams, values, and his world view to my five younger siblings, – I felt a weight of responsibility upon my shoulders.

At the same time, this emissary was a confused, introverted, shy boy who wanted to break out of the family and make his own mark on life. Having recently discovered, among his fun-loving, nihilist circle of friends, the magical anti-anxiety effect of drink and weed, he was torn between the call of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll, and his loyalty to a father he both loved greatly and feared somewhat.

Feeling like an imposter, I took each step with him, through the Testaments Old and New, the visits, the countless bedroom masses, and, as he got weaker, the shaves and bedpans. Though increasingly anxious as his health declined, I delighted in every moment spent with him, somehow believing that, through my boundless love, he could be saved.

Alas!

In the weeks leading up to the ambulance incident, he had placed great stock in his wish to die at home. I saw no reason why this wish could not be granted and assured him that it would. My assessment failed to consider the possibility of that decision being taken over my head. This is what had come to pass. My mother and older siblings had decided on `what was best´ for all concerned. The moment his weary glance met mine at the garden gate, I felt like Judas,The Betrayer – and the victim of ultimate betrayal, – at one and the same time. It would take many years for me to lance the boil of rage that began to take shape inside me that October afternoon.

Our bond seemed never as warm again after that afternoon. He spent the following weeks in a hospice across town. I visited him as often as possible during those weeks until he drew his final breath on November 10th, 1977. I was not with him in his final hour, waiting on tenterhooks at home for some sign per telephone as to his condition.

Looking back now, with the advantage of decades of life experience and reflection, I see that my father gave me the greatest gift anyone can ever bestow upon another, – a gift I continue to unpack to this day; he showed me how to leave this incarnation with grace and dignity. A free-spirited and nonetheless fervent doctrinal Catholic before falling ill, he had had a spiritual awakening between Easter and All Souls of his final year. In the end, he abandoned himself to his Maker in humility and gratitude, reassuring his loved ones that, of them too, loving care would be taken. I did not recognise the magnitude of his transformation at that time.

When the curtain fell, I was left behind on a stage empty and cold, feeling despondent, resentful, and very angry. My mother, with whom I had always had a very challenging relationship, was broken-hearted and, dictated by the dearth of capacity for mutual emotional support in our family, the aftermath of Dad’s passing became a case of `every man for himself´. When I entered the room in which the remains of my beloved father were laid out, immediately a thought struck me, like a bolt of lightning, before I even saw it coming: `Why Dad? – It would be better if Mammy were lying there instead!´

Guilt and shame flooded every cell of my body. I then despised myself and wished I had crossed over with him. I no longer saw any point in carrying on with the general humdrum of life. This is the poem I wrote in the week of his funeral:

Lower me down and let me lie

‘Mid walls of clay

And let the world whirl ‘round

Through night and day

While I lie

Motionless

Unconcerned and

Dead.

Lower me down

To my peaceful, eternal bed.

And as I lie

Lie with me

And we’ll gaze into one another’s eyes

And see

That lie of life.

We will to climb

But clay won’t hold

And we’ll fall e’en deeper

To lie once more.

And the world whirls ‘round.

The sun will rise, and

We will lie, exposed

To see again that lie.

Our eyes will close, and clay will fall

And………. and

The world will stop.

I carried the heavy burdens of suppressed grief, anger, and rage for the next quarter century, navigating my path by means of denial, over-functioning, and self-medication. This got me through to my early forties, when eventually, the house of cards came crashing down. It was only at this point that I was prepared to change. I quit drinking and using, asked for and accepted help, and began a process of recovery that continues to this day.

When we are children, we need, in order to flourish, a set of experiences flowing unimpeded through our veins. They could be described as follows: being seen and acknowledged, knowing I am safe, protected, and perfect in the reality of being valuable, vulnerable, imperfect, dependent, and spontaneous. When these needs are not met, whether by malice, inadequacy, or lack of awareness on the part of our adult carers, we lose our balance and develop survival strategies which, although they keep us afloat in the situation, invariably come back later in life to hurt us and our loved ones even more.

In the incident described above, my sense of value was violated. When this happens, it can have an immense impact on our sense of self esteem, usually sending the child into a vortex of alternating feelings of inferiority (less than) and superiority (better than).

Only when we work through the various voices we have internalised and arrive at a point where we esteem ourselves from within, can we find peace of mind and begin to unfold our full human potential. This presupposes stepping out of our active addiction dynamic(s) (both substance and process addictions) and engaging wholeheartedly in the work of recovery.

In my case the approach is a combination of three main components:

- Active Twelve Step Recovery

- Therapy, as needed, to address trauma & developmental immaturity

- Daily Positive Intelligence (PQ) Mental Fitness practice.

A key realisation in this respect is the need for action. Any transformation process, in order to succeed, is made up of 20% insights and 80% practice. Practice makes progress!

Today I am responsible for the maintenance of my Mental Fitness, and therefore my spiritual condition. All the resources required are available today as never before. For that I am most grateful.

In the Introduction to the Big Red Book of ACA (a Twelve Step Programme for those who wish to recover from growing up in a family characterised by dysfunction), published in 2006, we read the following: Adult Children (those in ACA recovery) are committed to halting the generational nature of family dysfunction for the greater good of the world. Recovery is possible. Our ACA recovery is not only for us, but is a service to humanity as a whole.

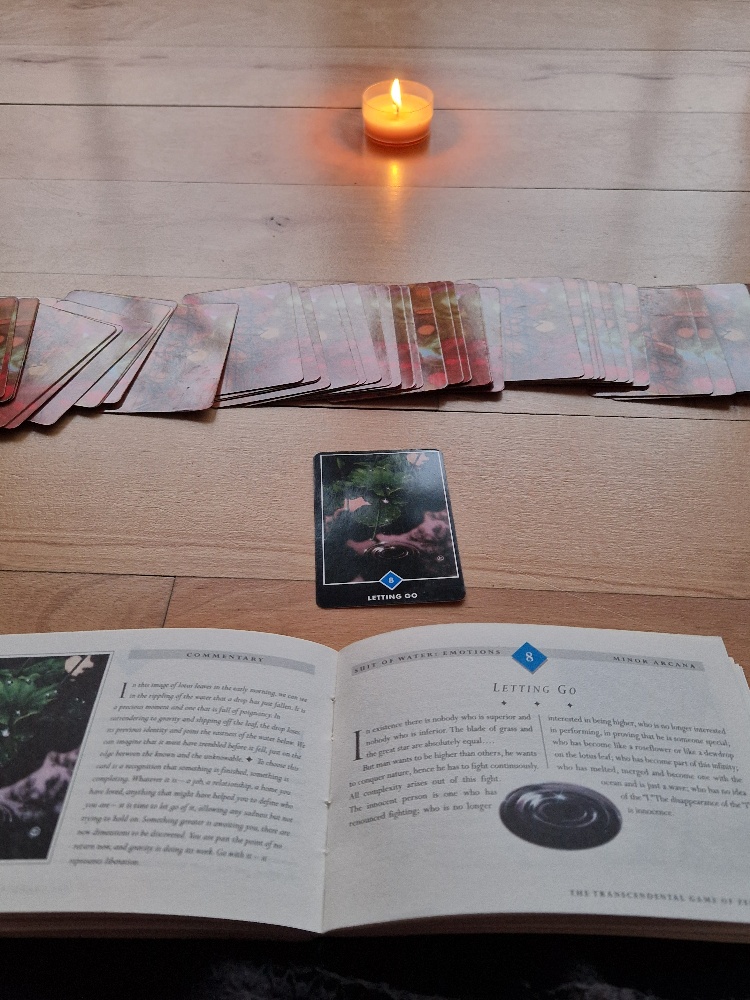

*Photo: South Pacific Private, Sydney, Australia. Screenshot from the YouTube video: `The Model Of Developmental Immaturity: Understanding Developmental Trauma and Recovery´